- Home

- John Lorne Campbell

Tales from Barra Page 2

Tales from Barra Read online

Page 2

I sent for the priest who was living at Iochdar, because he was a doctor, to restore me to health; when he was looking at me, my head was out of order; he said, ‘Death is coming for you, he will not leave you forgotten’ – My young brown lass.

Often I think of the men once alive, who used to drink and pay and would not leave me empty; if I knew that their souls were not in peace, it would be worthless work to be taking a dram, or drinking one at all.

My wife is worn out going through the land, collecting and seeking every herb that would make me perspire; in spite of her pain and her discomfort and her watching, in spite of her work, the joiner [himself] is nearly done for – My young brown lass.

But if my eyes are cured, I will make the attempt yet to go across the sound [Barra Sound] where is the dearest of men; where there is the chief of the clergy who does not expatiate on scarcity; little wonder your flock does not go one step into error – My young brown lass.’

Fr Allan says that, ‘The Siosalach and Griogalach were the Rev. John Chisholm of Bornish and the Rev. James MacGregor of Iochdar. The priest of Barra was the Rev. Neil McDonald who died afterwards at Drimnin, Morvern.’

The priest of Barra must, however, have been the Rev. Angus MacDonald, for whom Angus MacPherson went to work in 1819 at Craigstone.

The other song is:

‘Oran a rinn Aonghus Mac Caluim do sgothaidh a bha ’m Barraidh [deleted, Cille Brighide substituted] ris an canadh iad “An Cuildheann” – Coolin Hills.

Hug a rì hu gu gù rìreamh

Air a’ bhàta làidir dhìonach,

Do Not Faro ’s do na h-Innsibh

Bheir i sgriob o thìr a h-eòlais.

Thug iad an Cuildheann a dh’ainm ort,

Beanntannan cho àrd ’s tha ’n Alba;

Cuiridh canbhas air falbh iad,

Ged tha siod ’na sheanchas neònach.

Gaoth an iardheas far an fhearainn,

’S ise ’g iarraidh tighinn a Bharraidh;

Chuir i air an t-sliasaid Canaidh,

’S bheat i ’n cala gu Maol-Dòmhnaich.

Bàta luchdmhor làidir dìonach

Gum bu slàn an làmh ’ga dianamh;

bheat i na bha ‘n taobh-sa Ghrianaig

Ach a cunntas liad ’san t—seòl dhi.

Gaoth an iardheas as an Lingidh

Toiseach lionaidh, struth ’na mhire,

’S ise mach iarradh gu tilleadh

Ach a gillean a bhith deònach.’

Translation

‘A song which Angus son of Calum made to a boat which was in Barra (deleted, and Kilbride substituted – Kilbride is in South Uist) which was called The Coolins.

Chorus: Hug a ri hu gu verily

On the strong watertight boat

To Not Faro and to the Indies

She will journey from her own country.

They called you “The Coolins,” mountains as high as any in Scotland; canvas will set them moving, though that is a strange tale.

The wind is in the south-west coming off the land, as she seeks to come to Barra; she left Canna on her beam, and beat into harbour to Muldonich.

A valuable, strong, watertight boat, may the hand that made her prosper; she beat what boats there are on this side of Greenock, only counting the breadth of the sail in her.

The south-west wind is off the sound [between Barra and Vatersay], flood tide starting, current playing; she would not ask to turn back as long as her lads were willing.’

[A version of eight verses, but lacking the fourth verse given here, was printed by Colm O Lochlainn in Deoch Slàinte nan Gillean, in which it is stated that the song was made by the Coddy’s great-uncle to the boat in which he and the Coddy’s great-grandfather came from Mull to Barra; but this can hardly be the case, for it was the Coddy’s maternal great-grandfather Robert MacLachlan who came from Mull to Barra, not Angus MacPherson, the bard, though this boat might have brought them.]

‘Iain MacPherson (Angus’s son) settled in Brevig, had a boat which he built himself, and was drowned on the Oitir. After his death his widow (Mary MacNeil) was evicted from the house in Brevig and went to live in Bruernish, near Northbay.’

[Iain’s son Niall married Ann MacLachlan, as has been stated.]

‘When my father left school, he started work lobster fishing with his father, and later worked on Donald William MacLeod’s boats line fishing and herring fishing.’ Donald William MacLeod was married to the Coddy’s aunt. ‘Probably about this time he joined the Royal Naval Reserve. One summer he had a very severe attack of pneumonia, and after that did not return to the fishing. Instead, he started working for Joseph MacLean, one of the leading Barra merchants, and became his fish salesman. This work took him to Skye, Lochboisdale, and, of course, to Castlebay (which was then a great herring curing centre). In the off-season he worked at Skallary and Northbay. In 1911 he got a croft at Northbay, built a house and set up a merchant’s business of his own, and in 1923 he was appointed Postmaster of Northbay.’

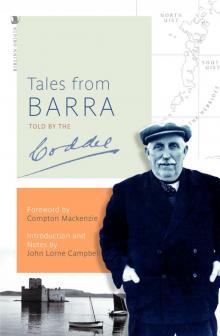

I continue the account with a quotation from the obituary printed in the Oban Times:

‘When cars came to the island he started a car and motor-hiring business with considerable success [actually I believe he had the first car ever imported into Barra, a model T Ford]. As the tourists began to flock to the island he decided to build a boarding house, and this was the “Coddy” in his element and at his very best. He was the genial host, the great story-teller and the charming fear-an-taighe. Many will remember pleasant hours spent in Taigh a’ Choddy listening to his fund of folk-lore told with feeling and sincerity. Most of these were told in Gaelic, but the “Coddy” was equally fluent in English.

‘It was not surprising to hear he had taken part in the film during the shooting of Whisky Galore on the island of Barra. In fact, with such a personality he could have had Hollywood at his feet. Indeed, it can be said that it is possible that the author would never have written the book if there had been no “Coddy”.

‘He served for a number of years on the Barra District Council and also on the County Council of Inverness, where he gave unstinted service to his island.

‘One of the many great qualities in his life was his devotion and loyalty to his church. He saw the church, St Barr at Northbay, go up, and he took a keen and leading interest in it all of his days. His fondness of children and his kindness and readiness to help when ever he was approached testified to his true Christian character.

‘In June 1944 he received a severe blow in the death of his second son, Neil, who was killed in action while serving with the R.A.F. This upset the Coddy very noticeably, and he was never quite the same again. For the past year he had been confined to the house with cardiac trouble, and the end came peacefully on the morning of 27th February, 1955.

‘After Requiem Mass in St Barr’s church, Northbay, he was laid to rest in the cemetery at Kilbar in Eoligarry, facing the Oitir Mhór of which he was so fond. To his widow and family of three sons and three daughters his very many friends offer their sincere condolences, and their farewell to the Coddy they express in the native tongue by that final prayer of the church:

Fois shìorruidh thoir dha, a Thighearna,

Agus solus nach dìbir dearrsadh air.’1

Coddy’s personality and talents as a host brought him before long a large number of visitors, some of them distinguished ones – their names are preserved in his green book – peers, politicians, officials, descendants of Barra emigrants to Canada and the U.S.A., scholars from Scotland, Norway and Gaelic Ireland, archaeologists, ornithologists, sportsmen and holiday-makers simply seeking a change and a rest in the peaceful unhurried atmosphere of pre-second war Barra, all made their way to the Coddy’s, attracted by his vigorous personality and the kindness and hospitality of his wife and family.

I did not know that Coddy’s house had become so popular when I returned to study colloquial Gaelic there in the summer of 1933. Conversation with English-speaking visitors, though often interesting, did

not further these studies very much. But Coddy was assiduous in his teaching. I got no English from him. ‘Abair siod fhathast, Iain,’2 he used to say to me whenever I made an error in pronunciation or used the wrong word. As autumn drew on, and the visitors departed southwards with the puffins and other migrants, we got more time to ourselves to study the language which we both loved.

Twenty-odd years ago Barra was an island where, one felt, time had been standing still for generations. It is always extraordinarily difficult to convey the feeling and atmosphere of a community where oral tradition and the religious sense are still very much alive to people who have only known the atmosphere of the modern ephemeral, rapidly changing world of industrial civilisation. On the one hand there is a community of independent personalities where memories of men and events are often amazingly long (in the Gaelic-speaking Outer Hebrides they go back to Viking times a thousand years ago), and where there is an ever-present sense of the reality and existence of the other world of spiritual and psychic experience; on the other there is a standardised world where people live in a mental jumble of newspaper headlines and B.B.C. news bulletins, forgetting yesterday’s as they read or hear today’s, worrying themselves constantly about far-away events which they cannot possibly control, where memories are so short that men often do not know the names of their grandparents, and where the only real world seems to be the everyday material one. If it be the case that ‘Gaelic alone is not enough to keep a man alive’ and that therefore the Hebridean world of oral tradition must yield to the encroachment of mass semi-sophistication and anglicised education, so that the islanders be not cheated in the labour markets of the south, that does not mean that victory is going to the ‘better’ of the two contestants in the struggle, but simply that the material progress of the Islands is being achieved at the cost of cultural impoverishment, which makes one envy the more the Icelanders and Faeroese who have contrived to make the best of both worlds, and are retaining their ancient languages as instruments of modern culture and education, while bringing their material way of life up to date.

In the Barra of Coddy’s time, psychic experiences were still sufficiently frequent to maintain the particular character these have always given to the Hebrides, as can be seen from his stories. Material events, such as the evictions, the potato famine, the departure of the last of the old race of lairds in the direct line, the Napoleonic wars and the oppression of the pressgang, none of which happened later than 1851, seemed to be matters of yesterday. The Jacobite rising of 1745 and 1715 felt only a little farther back, and the events of the seventeenth century, the wars between Royalists and Covenanters, and the visits to Barra of the Irish Franciscans (1624–40) and the Vincentians (1652–57), of whom Fr Dermid Dugan was particularly well remembered, seemed only a very little earlier. Behind all this lay memories of the exploits of the old MacNeils of Barra, of the Lords of the Isles, and of the Viking invaders of Scotland and Ireland, who started coming in the ninth century: the island of Fuday in Barra Sound is said to have been the site of the last surviving community of Norsemen in the Barra district.

Next to none of this information, it need scarcely be said, was derived from printed books, still less from the formal compulsory school education given on the island, which was entirely in English from its inception in 1872 until 1918, when Gaelic was admitted as a permissive subject, and where the teaching of history was heavily coloured with the pro-Whig and anti-Highland bias of the standard Scottish text-books. The vehicle of Barra tradition was the Gaelic folk-tale, the anecdote, and the folk-song, of which thousands existed; a rich and varied tradition, but one which, lacking patrons, brought its practitioners no material reward. Here it was greatly to the Coddy’s credit that, unlike some Gaelic-speaking Highlanders who have made their way in the world, he never turned his back upon the language and traditions of the race to which he belonged, but was fully aware of their beauty and did his utmost to encourage those who were trying to preserve these things and prevent them from falling into oblivion. In this my friends and I have been heavily indebted to him.

In 1933 there were living within two miles or so of Coddy’s house Ruairi Iain Bhàin and his sister Bean Shomhairle Bhig, the two most outstanding folk-singers I have ever listened to; Seumas Iain Ghunnairigh, an excellent story-teller; Murchadh an Eilein, born and brought up on the now uninhabited island of Hellisay, and full of interesting stories and local traditions; Alasdair Aonghais Mhóir, a famous character and gifted raconteur; Neil Sinclair ‘An Sgoileir Ruadh’ Schoolmaster at Northbay, descended from Duncan Sinclair who lived on Barra Head,3 a beautiful speaker of Gaelic who took a most intelligent interest in his native language and aided many of the Gaelic students who visited Barra; and many others, including Miss Annie Johnston, well known to many folklorists, who lives in Castlebay. Doyen of all these was Fr John MacMillan, parish priest of Northbay, a native of Barra, great in heart and in body, a wonderful preacher in Gaelic, and a true poet. No student of Gaelic could wish for better surroundings and company. Looking back on those days my great regret is that we had not the means to record these tradition-bearers adequately before the Second World War broke out. In those days such work was entirely unrecognised in Scodand, though this was not the case in other countries such as Ireland, Scandinavia and America. I remember very well trying, in 1938, to find an institution in Scotland which could accept copies of recordings of traditional Gaelic songs made in Nova Scotia the preceding year. I could find none which had any provisions for accepting such a gift.

The process of getting inside the tradition itself was by no means easy. First the local dialect had to be learnt; here ‘book Gaelic’ was an actual obstacle. All spoken Scottish Gaelic dialects differ from the literary language, in some respects consistently: the dialects of the Outer Hebrides are, in fact, more vigorous than the modern literary language, and contain many words and expressions that are not in the printed dictionaries.4

Coddy was assiduous in assisting these studies. We used to go together to the houses of Seumas Iain Ghunnairigh or Alasdair Aonghais Mhóir in the winter evenings, when the story-telling and exchange of reminiscences would soon begin. At first I could hardly do more than pick out an occasional word or sentence here and there. I was just beginning to feel that I would never do more than this when suddenly things seemed to become clear, although, of course, there were (and are) still many difficulties to be overcome.

In January 1937, much to the Coddy’s interest, I was able to acquire a clockwork Ediphone, after having first tried and discarded a perfectly useless phonograph recommended by some foreign authority. This Ediphone interested the Coddy hugely and he was assiduous in finding people to record on it. In particular, he was anxious for the songs of Ruairi Iain Bhàin to be recorded: for Ruairi was getting old; his sister Bean Shombairle Bhig, a wonderful folk-singer, who had sung, to Mrs. Kennedy Fraser, was in ill health and unable to sing again.

In July 1937 my wife and I, who had made our home in one of Coddy’s houses since 1935, left with the Ediphone to record old Gaelic songs from the descendants of Barra emigrants in Cape Breton,5 amongst whom we found the same songs still preserved by the old people; that is another story. On our return to Barra in 1938 I brought a Presto J disc recorder with which I was in time to re-record Ruairi Iain Bhàin and a number of other singers; some of these recordings with a book of words were published by the Linguaphone Institute in 1950, greatly to the Coddy’s joy. When I visited Barra again between 1949 and 1951 with a wire recorder, Coddy was again to the fore in encouraging the work, and recorded Gaelic versions of twelve of the anecdotes which are printed here. He realised perfectly well what so few realise: that the Gaelic oral tradition is an immense tradition containing many things of beauty and interest, and a great deal of it had already perished irrevocably, and that unless a desperate effort were made, most of the rest would perish too, especially the old songs in their authentic form. ‘Ah, Iain,’ he used to say, ‘if only you had come around with that machine tw

enty years ago, what wouldn’t you have got from the men and women who have passed away. You could never believe how much has been forgotten.’

In the spring of 1951 I made my last visit to the Isle of Barra with the wire recorder, accompanied by Mr Francis Collinson, who had just been given a Research Fellowship in folk-music at Edinburgh University. As usual, the Coddy was to the fore in encouraging the work and, of course, we stayed at his house at Northbay, where another visitor was Miss Sheila J. Lockett, on a holiday from London. After hearing some of the Coddy’s tales, Miss Lockett was so much struck by their interest and the vividness of the Coddy’s style, that she suggested they would be well worth taking down in shorthand. This was eventually arranged, and later in 1951 and in 1952 Miss Lockett made a number of visits to Northbay for this purpose, taking the stories down in the Coddy’s own words, just in time before his memory began to fail. Miss Lockett, whose name should be known to students of Scottish Gaelic folklore in connection with the part she has played in drawing the music which is printed in Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist, and in preparing this work and Fr Allan McDonald’s Gaelic Words from South Uist for the press.

A word on the history of Barra will not be out of place here, for it is a constant background to these stories. Traditionally the name of the island is associated with St Finbarr of Cork who lived in the sixth century. St Finbarr, whose story can be read in Charles Plummer’s Lives of the Irish Saints, was undoubtedly a powerful saint, but there is no record of his ever having been in Scotland. More probably the church was dedicated to him by one of his pupils. At any rate, the memory of St Barr is still vivid in Barra. Down to the seventeenth century it was popularly believed that dust from the burial ground named after him at Eoligarry, scattered on the sea, would result in the calming of storms, and even later his statue was preserved in the church there, as is mentioned by Fr Cornelius Ward (1625) and Martin Martin (1690). This statue, indeed, may still exist somewhere in concealment.

Tales from Barra

Tales from Barra